Appendix 7

A History of the early days at CHOM-FM

Taken from "Twenty- Five Spirited Years of CHOM-FM"

by Martin Melhuish 1994

If you had been walking down Greene Avenue on the evening of October 28, 1969, you might have bumped into a young man, his arms full of records, briskly striding towards the building that housed radio station CKGM and CKGM-FM. The weather was blustery and cold, but the young man in a knitted wool sweater and multi-colour patched blue jeans, with his waist-long hair flapping in the wind, was oblivious. He was a man with a mission - not impossible, but improbable - to plant a musical seed in what had proven to be barren soil at a radio station which itself was barely showing signs of life.

If you had been walking down Greene Avenue on the evening of October 28, 1969, you might have bumped into a young man, his arms full of records, briskly striding towards the building that housed radio station CKGM and CKGM-FM. The weather was blustery and cold, but the young man in a knitted wool sweater and multi-colour patched blue jeans, with his waist-long hair flapping in the wind, was oblivious. He was a man with a mission - not impossible, but improbable - to plant a musical seed in what had proven to be barren soil at a radio station which itself was barely showing signs of life.

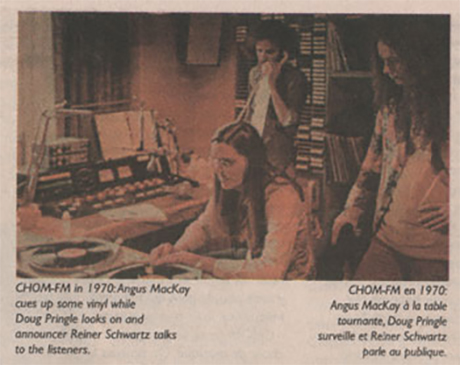

The young man's name is Doug Pringle, born to British parents in Calcutta, India, schooled in South Africa, Belgium and England and through a twist of fortune, by the late 60's, a resident of Montréal. Actually, Montréal was to have been only a stopover on his way back to England following a period of living, traveling and working in the U.S.

"I was actually living in Boston a the time and I had booked my passage back to England" recalls Pringle, who is now a consulting executive to one of Canada's most successful broadcasting companies. "Quite honestly, I hadn't even thought about visiting Montréal but, as it happens, the boat was to leave from there. I arrived two days early and fell in love with the city. I picked up an application form from Sir George Williams University before I left and when I arrived in England I got word that I had been accepted. I turned right around and emigrated to Canada."

Back in Montréal, Pringle got himself a little apartment and started classes at Sir George where he was a founder of TV Sir George as well as program director and on-air announcer at Radio Sir George. "I was playing all my own records to all those poor people eating in the cafeteria. As it turns out, everyone loved it because all of my friends were into the same kind of music I was and it was not available on the radio at this point."

It was with that in mind that one day Pringle wandered into CKGM-FM, the bottom-rated radio station in Montréal which was, at the time, playing easy listening music. He went armed with a proposal to broaden their listenership to the Montréalers of his age who he was sure were as passionate as he was about the broad spectrum of rock music that was emerging in the late 60's.

As it turns out, the station owner Geoff Stirling, was less that enthusiastic about what was going on at the station at the time and decided to let Pringle test the waters with a four-hour show with was to run from 11:00 pm until 3:00 am. That show was taped and repeated from 3:00 am until 7:00 am. "We'll give it a shot," said Stirling, "but if you're full of shit, you're out of here."

So at 11:00 pm on that cold and windy fall evening of Oct 28, 1969, Pringle took to the air to the sounds of Thus Sprach Zarathustra. That segued into Here Comes the Sun by the Beatles, which became the first song to play on the station which would shorty evolve to CHOM-FM, L'Espirt de Montréal.

Progressive rock radio had come to Montréal and, as Pringle predicted, the phones lit up with supportive calls from Montréalers, both English and French, who had been searching for the music and artists, many of whom had been show-cased at Woodstock and the other festivals that summer. Within a month, a second announcer, Greg Schifrin, was added to the station and Pringle moved up to 7:00 pm with his four-hour shows. "It was my taste in music for four hours and then it was Greg's, which was far more blues based, then my show repeated again. After about three months, we went 24 hours a day with the format which was originally positioned as Tribal Rock, complete with the sound of tribal drums."

Today the phrase is likely to conjure up images of wild-eyed, drugged-out hippies in loins cloths dancing around an open fire, but there was another side of the culture which was defined by those in search of a spiritual base for their lives.

Pringle says: " What set CHOM apart from all of the other progressive rock stations like KSAN in San Francisco, CHUM-FM in Toronto, CFOX-FM in Vancouver, and WBCN in Boston was that it was based as much on spirituality as music.

"I always considered the flagship show on CKGM-FM to be The Spiritual Hour which was at 8:00 pm on Sundays. The only thing it never was was an hour. It went on as long as it went on. I hosted the show but sometimes it would just be Baba Ramdass tapes or commentary from visiting holy men, Swamis and Tibetan Lamas. It really was the North American media home to all of the spiritual beings who were wandering all over North America spreading the word. They knew that in Montréal there was a friendly place where they could come and relax and get on the radio, talk to people and share their ideals and their beliefs."

Along the way it was decided that a new home and a name change was needed for the station because sister station CKGM-AM was playing Top 40 pop music which in those days was considered extremely crass. No one wanted to be tarred with that brush. As they discussed the choices for a new name, the one thing they knew it had to have was a spiritual context. The two finalists became CHID-FM after Swami Chidanada and CHOM-FM after the cosmic matra "Om". These deliberations were going on as Geoff Stirling and Doug Pringle set out on a three or four month pilgrimmage to India.

By the time they had returned to Montréal, Stirling had decided that the name of the station was to be CHOM-FM.

"One of the great things about Geoff was that when we started at CKGM-FM, he really didn't ask us to make money," says Pringle. "He just asked us to break even. As a group, we had control over what we would and wouldn't do. In terms of the advertisements that we would accept on the air, it was very limited. We weren't into beer because we were all smoking dope. Car ads were out because the polluted the atmosphere. Outside of head shops and record stores, there wasn't an awful lot of advertising that the group of us could agree on. We had Sherman's, the record retailer, advertising with us at one point, that was until they put in a turnstile into their store so you couldn't get out of the store without going past the cash. The was cause for an immediate group meeting and, in the end, Sherman's ads got dropped because we felt this showed a lack of trust in their fellow man. In those early days, there wasn't a great deal of advertising on the air, not because the station wasn't popular, but because there weren't a whole lot of products that could live up to our high ideals."

Stirling went along with this strict ad policy for a longer period of time than anyone else in radio would have, but finally even his patience wore thin. One day he came to town for the customary board meeting. Recalls Pringle: "We had expected Geoff to say the usual stuff like, 'Well, I'm not expecting to make money but at least try to break even,' but this time he simply said, 'Okay, you're all fired!' Well, you could have heard the jaws hit the table. Then he went on to say, 'Now look, I've got this great little radio station. You pretty much get to do whatever you want. You get to play whatever music you want to play. It's really fun. There's only one slight drawback. You've got to accept advertising. Now, who would like to work for this radio station?' Sheepishly, everyone put up their hands. From that day one, things were a lot different on the advertising front."

When CHOM finally moved into its new Green Avenue headquarters just up the street from its original home, the front door was specially commissioned to be made with a glass heart to signify the heart that was in the radio station, (That door is still part of CHOM's production facility at its present address on Greene Avenue.) "it really was a radio station that had more heart that any other I've heard because it was founded on such spiritual giving principles. While nearly all the other progressive rock stations were smoking their brains out and dropping acid all over the place, CHOM probably had more people not doing drugs because of the number of people who were into mediation. Of course, with meditation the first thing you do is stop taking drugs. I'm not saying there wasn't a ton of drugs being done but there were also a lot of people into the mediation side of the movement."

Musically, CHOM was extremely eclectic. You could hear everything from 18-minute ragas from Ravi Shankar to Motown music. "A brand new Stevie Wonder album was a much a big deal as a brand new Led Zeppelin or Jimi Hendrix record. Great black music and artists like Taj Mahal were superstars. Donovan's From a Flower To A Garden was a gigantic album. The Incredible String Band was huge on CHOM as were Tyrannosaurus Rex, even before they before they became T. Rex. Harmonium, who became the first French Canadian super group, did a live show on CHOM before they had a record contract. Many of the early French Canadian band got their only play on CHOM before the French stations picked up on them. At one stage, we sat down and talked about what CHOM needed to do to continue to be L'Esprit de Montréal. How could you be L'Esprit de Montréal if you didn't have the French Canadian totally represented.

Musically, CHOM was extremely eclectic. You could hear everything from 18-minute ragas from Ravi Shankar to Motown music. "A brand new Stevie Wonder album was a much a big deal as a brand new Led Zeppelin or Jimi Hendrix record. Great black music and artists like Taj Mahal were superstars. Donovan's From a Flower To A Garden was a gigantic album. The Incredible String Band was huge on CHOM as were Tyrannosaurus Rex, even before they before they became T. Rex. Harmonium, who became the first French Canadian super group, did a live show on CHOM before they had a record contract. Many of the early French Canadian band got their only play on CHOM before the French stations picked up on them. At one stage, we sat down and talked about what CHOM needed to do to continue to be L'Esprit de Montréal. How could you be L'Esprit de Montréal if you didn't have the French Canadian totally represented.

"From that meeting came our decision to hire our first French Canadian announcer, André Rheaume. After André, there was a great tradition of French announcers like Bob Beauchamp and Bobby Boulanger. I had learned French when I was growing up and lived with a French family in Paris and there were a few other English announcers who could speak it as well. What developed was a sort of Franglais where we could literally start out a sentence in one language and then switch back and forth. What we started getting on the radio was a real feeling of the city of Montréal. There were some pretty strange politics happening at the time, yet there was an absolute feelling of oneness in a culture that was much bigger than even the English or French Canadian culture. It was the hippies who have now become the yuppies. It was the counter culture being born and that superseded the French and English culture (the bands were beyond being English or French.) The biggest bands of that time where all English band - Pink Floyd, Supertramp, Genesis, Gentle Giant an so on. When they came to play in Montréal, you never saw so many Union Jacks being waved by French Canadians. I always though it was the living example of how all of Canada should be or could be. There was a wonderful spirit of giving between both cultures. It really felt like CHOM didn't belong to one culture in Montréal any more than the other."

As the station's stature grew within rock music circles around the world, more and more artists sough out CHOM when it came time to spread the word about the latest developments in their career. Pringle recalls one particular trip to Montréal by John Lennon and Yoko Ono as one of the most memorable of these visits. "Their train pulled into Central Station, just under the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, and we ran Bell telephone lines down to the train and plugged them into their railway carriage. We did a fairly lengthy interview on the air and of course the whole city was going crazy because John Lennon was in town and nobody knew where the hell he was. When we had finished, we unplugged the phone lines, the train rolled back to New York without John and Yoko ever setting a foot in Montréal. They had come specifically to be interviewed on CHOM and then they were off."

One of CHOM's most recognizable and enduring on-air ID's, the pleasant little ditty that sounds like someone singing "CHOM, CHOM...CHOM, CHOM" has and interesting story attached to it. One night Pringle had gone to see a James Coburn movie called Duck, You Sucker! at the old Greene Avenue Theatre. The lead actor's on-screen name was Sean. "I was sitting there and this music comes on - it was by Ennio Morricone I think - and all of a sudden I'm hearing, "CHOM, CHOM...CHOM, CHOM,' Actually they were singing, "Sean, Sean...Sean, Sean' but it was a butch of Italians with accents that made it sound like CHOM. My mind was exploding and I was seeing this whole thing. I couldn't wait to get out of the theatre to buy the soundtrack album. I know that if you took that short phrase out of context nobody would hear 'Sean', they'd hear 'CHOM'. I was also thinking of the concept of making 'CHOM' three-dimentional by adding sound effects like doors opening and birds twittering. It was all right there."

Thinking back to those days at CHOM, Pringle characterizes the station as incredibly musically self-indulgent. "Everybody was playing whatever they wanted and didn't care much about what the audience wanted to hear. It meant that if an announcer had a commercial taste in music , his or her show would be very well-rated. You'd see huge variations in rating from show to show in those early days because of that."

Taken from Time Magazine

August 1970

Free-form FM

Listening to FM radio can be a depressing experience, somewhat like being condemned to an exclusive diet of rusks. Those early promises by FM operators to promote High Culture have long since turned into an attitude of devil take the Hindemith. Instead, most stations content themselves with the kind of unmusic that is heard in steak houses and airport lounges. At Montreal's CKGM-FM however, the blandness stops. CKGM-FM gives the impression of emanating from a smoke-filled crash pad. Talk is sporadic and mostly aimless, and if the station had a call sign it would be a cross between a giggle and a mumble. Programming is equally informal: hours of Bob Dylan, acid rock or early blues may be interspersed with meditation chants, Lone Ranger recordings, sermons on cosmic consciousness or perhaps a replay of Orson Welles' classic 1938 "documentary" on the arrival of the Martians. Advertising is notable for its infrequency and for the fact that announcers will sometimes follow a commercial with an audible shudder.

It is hardly surprising, therefore, that CKGM-FM makes no money. What is remarkable is that the station is the property of Geoff Stirling, 48, a Newfoundlander with a reputation in broadcasting of being a hustler extraordinary. Stirling was the kind of child, who, at age ten, was telling people he would make his first million by the time he was 30. He did too. At 24, Stirling launched Newfoundland's Sunday Herald, a successful weekly tabloid, crammed with local gossip, and man-bites-dog yarns. Since then, he has branched out into real estate, bowling alleys, cattle holdings, seven radio stations in Newfoundland, Quebec and Ontario, and a TV channel in St. John's. Stirling started CKGM-FM in 1959, introducing breathless, hard-sell radio to Montreal and then hiring the late, ferocious Hot-Liner Joe Pyne. Over the years, CKGM developed a tradition of verbal thuggery that reached a zenith of sorts with Pat Burns, an exile from Vancouver who became a Francophobe messiah of English Montreal's "little people". Burns finally talked himself out of a job in June, 1969.

Why Stirling's sudden change of pace? The answer seems to be he found religion, Indian-style. An enthusiastic convert to transcendental meditation, the entrepreneur now asks such questions as "Is the only aim to accumulate more, like squirrels?". Obviously not, since at CKGM-FM, anyway, Stirling is not interested in a profit, only in breaking even. Last October, he began his experiment in free-form radio by hiring Doug Pringle, an Englishman with a Home Counties accent and Pre-Raphaelite hair. Now, the station has six announcers, who are given $125 a week and complete freedom on their four-hour slots. Stirling will send the occasional memo quoting Guru Kahlil Gibran to the effect that money is not love, then telling his staff to cut costs. They in turn have created the authentic and fashionably incoherent voice of a subculture. CKGM's eclectic music bears no relation at all to the banalities of Top 40 broadcasting. And the station's "message" which emerges from the formulate phrases of the announcers' hip jargon, is equally uncommercial. "Don't hassle us," they say, "Whatever your trip is, it's all right."

Among Montreal's English-speaking youth, CKGM-FM has an almost Pied Piper appeal. "It's the only station that cares about us," says a long-haired 19-year-old laborer. "The only one I can listen to," echoes a Montreal college girl. The station has a least one thoughtful adult supporter, Neil Compton, a professor of English at Sir George Williams University and TV critic of New York's Commentary magazine, likes CKGM-FM and sees the "almost ostentatiously clumsy and inarticulate" approach of the announcers as "a movement away from confidence in language." Such use of language, he concludes, is "preferable to the use of language in commercial hype stations. It only tells its listeners what they want to hear, never challenges them." Perhaps both are right. Compared with the blandness of most FM stations and the crassness of the commercial AM stations, CKGM-FM is an attractive alternative. Yet given a regime with total freedom, the final product is not nearly as stimulating as it might be.